Bengt J. Olsson

LinkedIn: beos

X/Twitter: @bengtxyz

Looking at aggregated data from Energy-Charts can provide valuable system-level insights. In this analysis, focus is on the ALL Europe dataset, which aggregates electricity production and consumption across all European countries covered by Energy-Charts.

This results in a very large and rich dataset. Since all included countries are electrically interconnected (unfortunately Great Britain is missing), imports and exports largely cancel out. As a result, ALL Europe can be treated as a single, closed power system with no net imports or exports.

Actual exchanges with regions outside the dataset are very small and can safely be neglected here.

TL;DR — Key result

Europe’s power system still relies heavily on fossil power for balancing.

Removing it without simultaneously reducing residual load variability implies a massive, and largely unresolved, challenge.

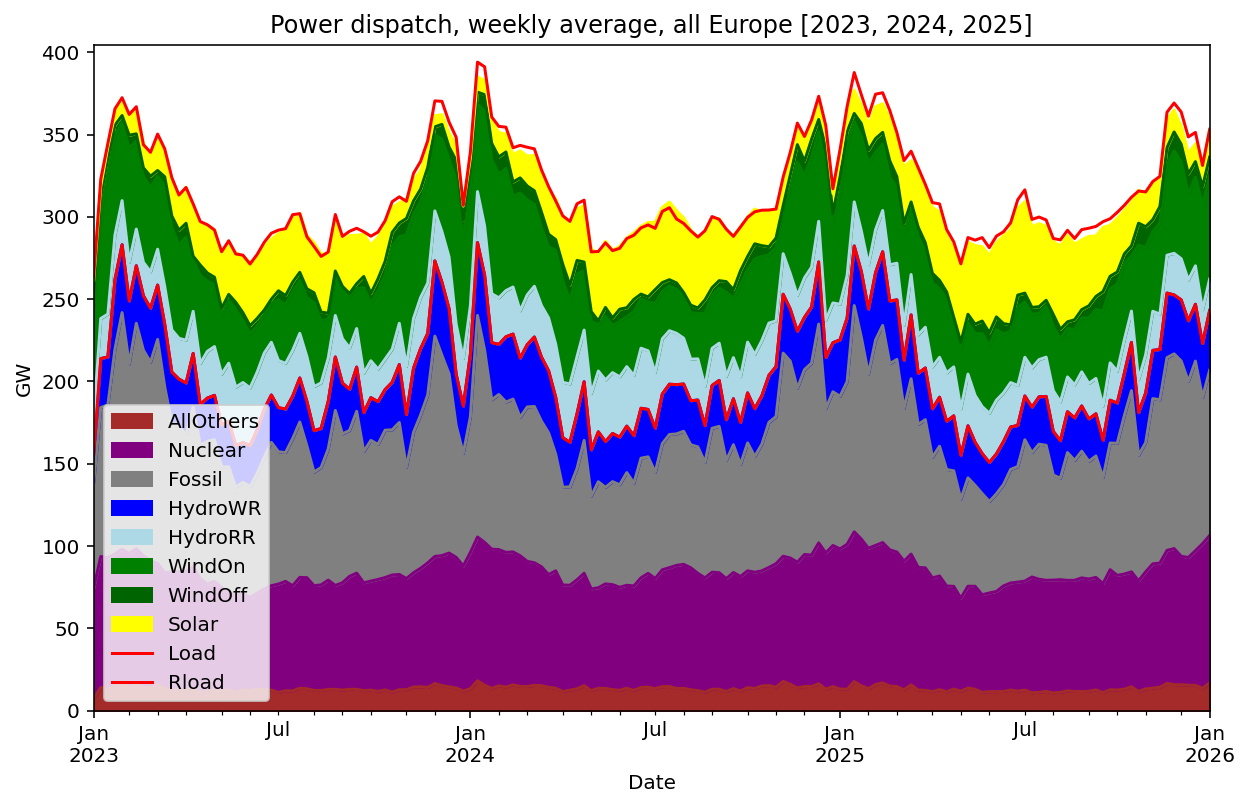

Aggregated Power Dispatch

Annual Energy Production

+--------+---------+----------+-----------+-----------+----------+-----------+---------+-----------+-------------+--------+

| Year | Load | Fossil | Nuclear | HydroWR | WindOn | WindOff | Solar | HydroRR | AllOthers | diff |

|--------+---------+----------+-----------+-----------+----------+-----------+---------+-----------+-------------+--------|

| 2023 | -2735.4 | 809 | 612.2 | 268.3 | 419.5 | 52.7 | 200.1 | 239 | 103.2 | -31.4 |

| 2024 | -2777.3 | 737.2 | 641.4 | 279.7 | 421.3 | 61.7 | 240.1 | 262.3 | 108.3 | -25.3 |

| 2025 | -2794.8 | 766.9 | 637 | 267.7 | 409.2 | 63.3 | 284 | 212.9 | 107.2 | -46.6 |

+--------+---------+----------+-----------+-----------+----------+-----------+---------+-----------+-------------+--------+

Yearly energy production (TWh) by power source for the ALL Europe area. “All Others” groups smaller and more diverse technologies. The difference relative to Load should ideally be zero, but deviates by about

1–2 % due to reporting inaccuracies. This has negligible impact on the results.

Most notably, Solar energy has soared during the investigated years. This is clearly visible in the dispatch graph as well. Less hydro and and wind production in 2025 has been balanced by more solar and, unfortunately, fossil power. Otherwise the production patterns are relatively stable over the years.

Balancing Europes power system

A particularly interesting question is how variable renewable energy is balanced by dispatchable power sources. For this purpose, generation technologies are grouped as follows.

Renewable (Must-Run) Sources

- Onshore wind

- Offshore wind

- Solar

- Hydro run-of-river

Dispatchable and Other Sources

- Fossil

- Pumped hydro

- Hydro reservoirs

- Nuclear

- All Others

The All Others category is dominated by biomass and waste. Batteries are excluded from the analysis since they currently contribute a negligible amount of energy at the European scale. In addition, battery reporting is still immature, with inconsistencies such as reported output exceeding input by roughly 35 %.

Quantifying Balancing Contributions

To quantify the balancing contribution of each dispatchable source, the covariation between each source and the residual load is calculated.

Residual load is defined either as:

- Load – Renewable, or “must-run” generation, or equivalently

- The sum of all dispatchable power sources

As is clear from the dispatch graph above, both definitions are identical.

Using the second definition, it can be shown that:

Var(Residual Load) = Σ Cov(Residual Load, Dispatchable Power)

where the sum runs over all dispatchable sources.

This allows us to attribute the total variance of residual load to individual balancing technologies, by calculating the covariance between residual load and the balancing technology in question. The analysis is performed over five different time horizons:

- Hourly

- Daily

- Weekly

- Monthly

- Quarterly

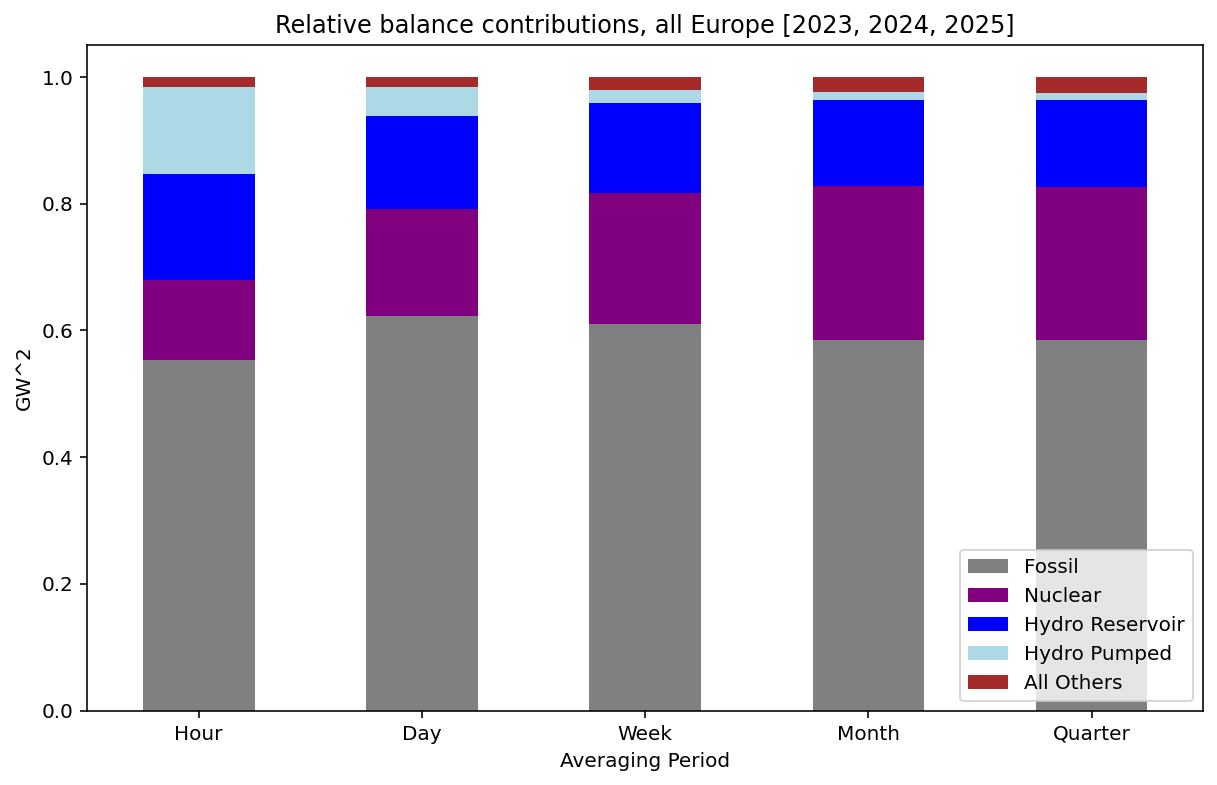

Balancing Contributions by Time Scale

Discussion

Fossil Power

Fossil power currently provides around 60 % of all balancing power, consistently across all time scales. It remains the dominant flexibility source in the European power system.

Pumped Hydro

On short (hourly) time scales, pumped hydro contributes noticeably, but its limited energy endurance restricts its role at longer horizons.

Hydro Reservoirs

Hydro reservoirs provide a remarkably constant balancing contribution across all time scales. Their limitation is not flexibility but scalability — it is difficult to significantly expand this resource.

Nuclear Power

Nuclear power contributes significantly to balancing, primarily through seasonal operation patterns: high output during winter and reduced output during summer maintenance periods, when residual load is lower.

Interestingly, nuclear also contributes down to hourly time scales. This is likely driven by the French nuclear fleet, which to some extent operates in load-following mode.

On seasonal time scales, nuclear is the second-largest balancing contributor after fossil power.

Biomass and “All Others”

The All Others category, dominated by biomass, contributes mainly at the seasonal scale. This is likely due to combined heat-and-power plants producing more electricity during winter, when heat demand and residual load are both higher.

Time Scales and the Nature of Balancing

Two distinct time scales with markedly different behavior emerge from the analysis:

hourly/daily and monthly/quarterly, with the weekly scale lying somewhere in between.

Shorter time scales — hourly and daily — can in principle be balanced using short-duration energy storage, such as pumped hydro or batteries. These technologies are well suited to managing intra-day variability and short-term forecast errors.

The monthly/quarterly, or seasonal, time scale poses a fundamentally different challenge. Seasonal balancing requires persistent energy storage, capable of shifting large amounts of energy across weeks or months. (Refer to the “Virtual store” section below).

If fossil power is excluded, hydro reservoirs cannot be significantly expanded, and nuclear capacity is not allowed to grow, the remaining option is essentially limited to large-scale hydrogen storage, combined with non-fossil gas turbines for dispatchable power.

Such a solution would require the build-out of an enormous hydrogen infrastructure, spanning production, storage, transport, and conversion back to electricity. At present, this remains largely unproven at system scale and faces substantial technical, economic, and regulatory challenges — even before large-scale deployment has begun.

Given these constraints, the most plausible outcome is that variable renewable generation will continue to be balanced primarily by fossil power, though increasingly in the form of natural gas rather than coal.

The Coming Balancing Gap

It is clear that as fossil power is squeezed out of the generation mix, it will leave a large gap in balancing capability. The challenge is compounded by two opposing trends:

- Residual load variability increases with higher shares of wind and solar.

- The largest flexibility source — fossil power — is simultaneously being removed.

What will replace it?

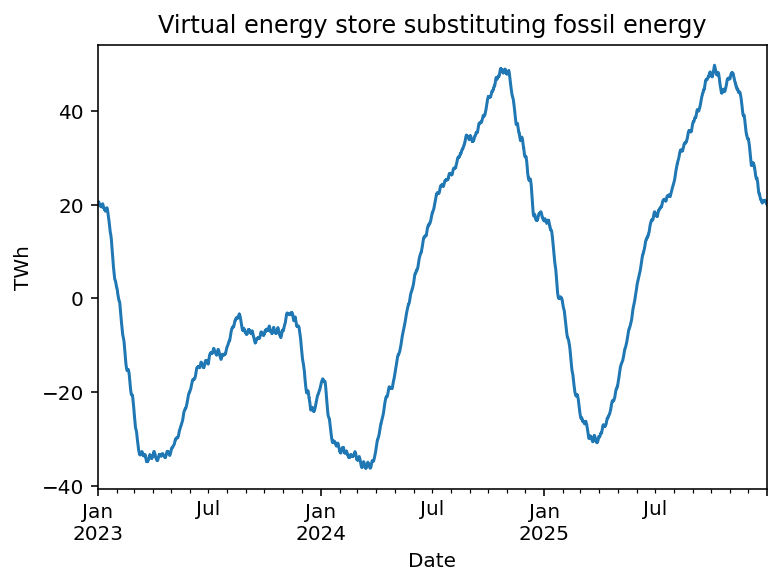

A Virtual Fossil Fuel Store

If we imagine fossil energy as being supplied from a large virtual store — filled continuously at a rate equal to average fossil consumption and emptied according to actual dispatch — we obtain the conceptual storage shown below.

To replace fossil power, an alternative dispatchable resource must be capable of storing energy at comparable scales. Moreover, the energy levels shown must be divided by the efficiency of the replacement technology, implying even larger required storage volumes, than the 86 TWh size shown in the graph. Also, if the store is charged variably in time, as it would be if weather dependent power sources are used for charging, the storage size would increase significantly.

How large is a 86 TWh electrical store? Well, it would take 10 nuclear power plants, each with 1 GW output, to run continuously for 1 year to charge that “battery”. Or, comparing with existing stores, more than what all the hydro reservoirs in Norway can hold. It is a lot of energy to store…

Nuclear Power as a Structural Balancing Resource

One could of course argue that replacing fossil power to a large extent with nuclear would fundamentally alter the system dynamics. A power system with a lower share of variable renewables would naturally exhibit smaller residual load variations, and hence require far less balancing capacity. In that sense, nuclear does not only replace fossil energy to abate carbon emissions, but also substitutes part of the balancing function itself.

Key takeaways

- Europe functions as a closed power system at the continental scale.

When aggregated to ALL Europe, imports and exports largely cancel out, meaning that balancing must be solved internally rather than via trade. - Fossil power remains the dominant balancing resource.

Around 60 % of residual load balancing across all time scales is currently provided by fossil generation, making it the single most important flexibility source today. - Balancing is a time-scale dependent problem.

Short-term variability (hourly/daily) can be addressed with short-duration storage such as pumped hydro and batteries, while seasonal (monthly/quarterly) balancing requires persistent energy storage. - Hydro reservoirs and pumped hydro are valuable but constrained.

Reservoir hydro provides stable balancing across all time scales, but is difficult to expand further. Pumped hydro is effective at short horizons but limited by energy endurance. - Nuclear power contributes more to balancing than commonly assumed.

Beyond seasonal effects driven by outage scheduling, nuclear also contributes down to hourly time scales, likely due to load-following operation in parts of the French fleet. - Removing fossil power creates a structural balancing gap.

As variable renewables increase residual load variability, the simultaneous phase-out of fossil power removes the largest existing flexibility source. - Replacing fossil flexibility implies storage at unprecedented scales.

The virtual fossil fuel store illustrates that replacing fossil balancing would require order of a hundred of TWh of storage, even before accounting for conversion losses. - Technology choice affects system variability, not just emissions.

A system with a higher share of nuclear and a lower share of variable renewables would exhibit smaller residual load variations, reducing the overall need for scarce balancing resources.

In short: decarbonisation is not only about replacing energy sources, but also about replacing flexibility — and the scale of that challenge is often underestimated.