Bengt J. Olsson

Twitter: @bengtxyz

LinkedIn: beos

(This newer post extends the analysis to a three zone market).

It is not easy to understand how prices on the electricity market are formed. At its core, the market matches supply with demand in an optimal way (whatever that means…). Here, we will examine what this matching looks like for two markets (or electricity areas) that are connected by a link. Even a system as simple as this becomes complicated when you examine the details. Therefore, functions as simple as possible have been used to make it possible to analytically calculate how the connection between the markets behaves.

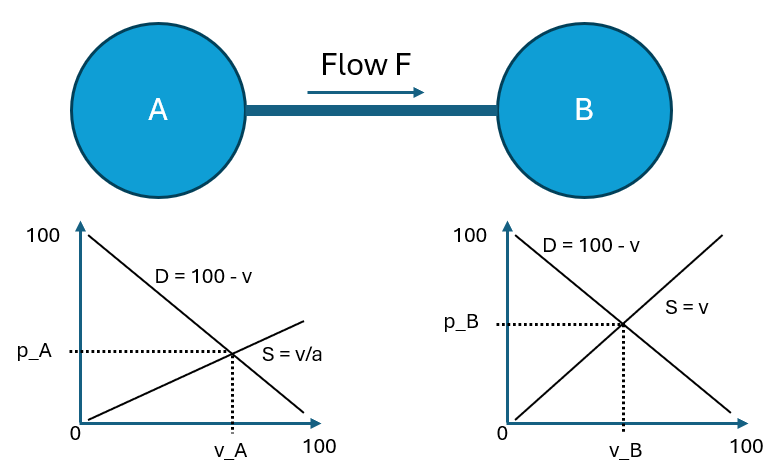

The model above contains two electricity areas, A and B, each with a supply and demand curve. These are chosen as linear continuous functions to make it as easy as possible to calculate. In reality, both supply and demand are made up of discrete bids, but when these are arranged, they form curves similar to those in the diagram, so for our purposes it is fine to approximate the bids with functions as in the picture. Supply and prices can, for example, be MWh and EUR/MWh, but we will calculate unitless.

Area B has a demand D = 100 – v, where v is the volume demanded at price D. The supply is simply S = v. We can see it as having an infinite number of electricity producers, each offering a small volume, each at a slightly higher price. The supply matches the demand at the point (v_B,p_B). That is, buyers and sellers meet at the volume v_B and the price p_B. v_B and p_B are determined by 100 – v = v => v_B = 100/2 = 50 => p_B = 50.

v_B = 50

p_B = 50

Area A has the same demand (100 – v), but a slightly cheaper production, modeled as U = v/a, where a is a parameter. This gives the intersection point

v_A = 100 / (1 + 1/a)

p_A = 100 – v_A

A is cheaper than B, with a=2

Here we will use a = 2 which gives the equilibrium point

v_A = 66.67

p_A = 33.33

So we have two areas with prices of 33.33 and 50 respectively. Area A is cheaper than area B. If we connect these, then, according to common theory, electricity should flow from A to B until the prices equalize (given that the flow F has no restriction). We will investigate this in two ways.

- We use A and B, but add a flow F between them and vary the flow.

- We make a new market, AB, which is the union of A and B. That is, we combine purchase and sale bids from A and B and create only one market where there is no flow restriction. And investigate what the equilibrium looks like in that market. That market is simpler, there is only one equilibrium price, so it becomes a kind of a “canonical answer” to compare the first calculation with.

The “welfare” of the system

Another aspect that we will look at is the so-called utility maximization. Utility (or “welfare”) in the system is defined as consumer surplus + producer surplus + congestion rent. Consumer surplus is the “utility” that consumers who buy electricity get when they pay a lower price than they bid in. For example, in area B, the consumers who ultimately get to buy electricity (i.e. have bid in at a price above p_B) have a total utility given by the area between the demand (100 – v) and the price p_B (which is 50). In this case, it becomes the area of a triangle, (100-50)*50/2 = 1250. In the same way, the producer surplus becomes the area between the supply (v) and the price (50). In B, which is symmetrical, it also becomes 1250.

When we then connect the two areas, a utility (“congestion rent” or “flaskhalsintäkter” in Swedish) is added when electricity flows from the cheaper to the more expensive system, it is defined as F*(p_B – p_A), i.e. the flow times the price difference in the areas. It represents the utility of redistributing resources (the details are for an economist to explain…). But we can also see that this part disappears when the flow F = 0 or the prices equalize (p_A = b_B).

The Total Welfare or Maximum Utility of the system is

Consumer Surplus in A + Producer Surplus in A + Consumer Surplus in B + Producer Surplus in B + Congestion rent

We’ll also look at an example when maximizing this function provides the prices and net positions of (here, flow between) the two areas.

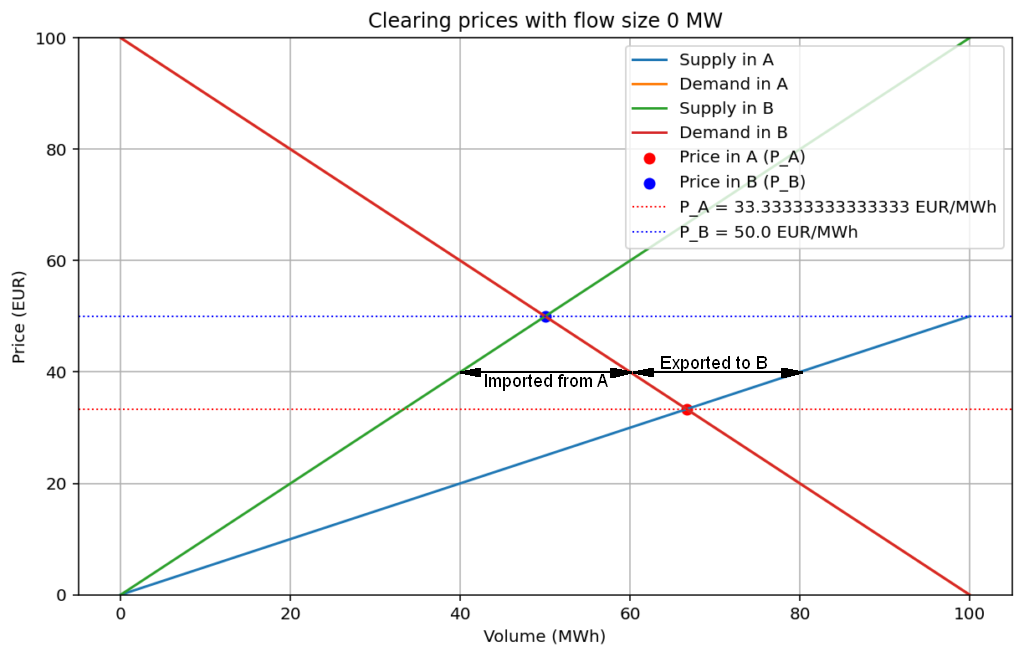

Flow between A and B is zero

a = 2

F = 0

In this case, we have two separate areas as above where B is more expensive than A.

Flow F A->B 0.00

Price in A 33.33

Price in B 50.00

Total volume 116.67

Consumer Surplus in A 2222.22

Producer Surplus in A 1111.11

Consumer Surplus in B 1250.00

Producer Surplus in B 1250.00

Consumer Surplus 3472.22

Producer Surplus 2361.11

Congestion Rent 0.00

Total Welfare 5833.33

Adding flow between A and B

When a flow from A to B is added, the demand and supply for each area changes in order to accomodate for the implied export from A and import to B. Prices are increased in A such that an excess of power, F, is delivered to B. In the same way, prices in B are lowered which creates an increased demand. The new equilibrium prices and volumes are now goverened by these modified equations:

A: 100 – v = (v + F)/a

B: 100 – (v + F) = v

If we now add a flow F of one unit (1 MWh here) we get the following situation:

Flow F A->B 1.00

Price in A 33.67

Price in B 49.50

Total volume 116.83

Consumer Surplus in A 2200.06

Producer Surplus in A 1133.44

Consumer Surplus in B 1275.12

Producer Surplus in B 1225.12

Consumer Surplus 3475.18

Producer Surplus 2358.57

Congestion Rent 15.83

Total Welfare 5849.58

Total Welfare 5849.58

To flow over 1 unit from A to B lowers the price in B, raises the price slightly in A, increases the total volume, and increases the total utility slightly. So it seems good. We continue by flowing over 20 units from A to B:

Flow = 20

Flow F A->B 20.00

Price in A 40.00

Price in B 40.00

Total volume 120.00

Consumer Surplus in A 1800.00

Producer Surplus in A 1600.00

Consumer Surplus in B 1800.00

Producer Surplus in B 800.00

Consumer Surplus 3600.00

Producer Surplus 2400.00

Congestion Rent 0.00

Total Welfare 6000.00

With flow 20, the prices between A and B have completely evened out to 40 in both areas. The new prices create a surplus of 20 in A and a deficit of 20 in B. The flow of F = 20 from A to B cancels this imbalance in both areas. The total utility is now up to 6000. The utility for customers in the more expensive area B has increased at the expense of customers in area A (and of course producers in area B). As expected, producers in A and consumers in B are winners in this redistribution.

How did we arrive at F being exactly 20 to achieve price equalization? Well, by trial and error. But we could also have obtained it by maximizing the utility function with respect to the parameters that can be varied in the model. In this model, given that supply and demand are given, only F can be varied. So in theory, we should be able to find maximum utility by deriving the utility function with respect to F and setting the derivate function to zero and solve for F. Doing it analytically, even in this simple case, becomes too complex (maybe someone wants to try?) But we can see what the utility function looks like on each side of F = 20:

F = 19 => utility = 5999.58

F = 21 => utility = 5999.58

so it seems that the welfare 6000 obtained for F = 20 is also the optimal welfare. (Also a straight numerical optimization of the total welfare with respect to F, provides F = 20. At the end we look at such an example).

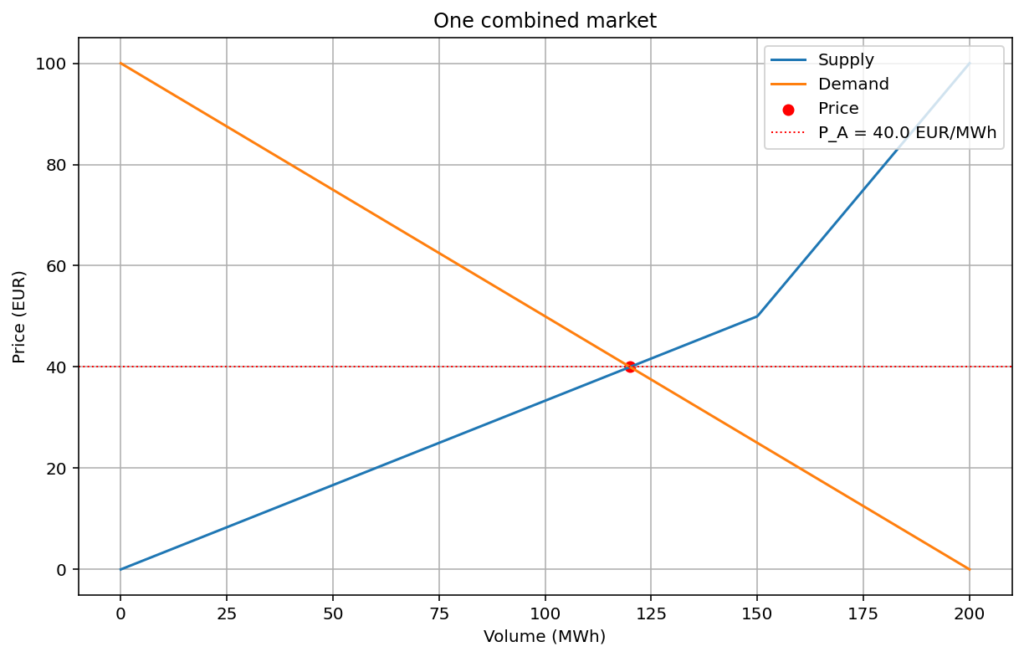

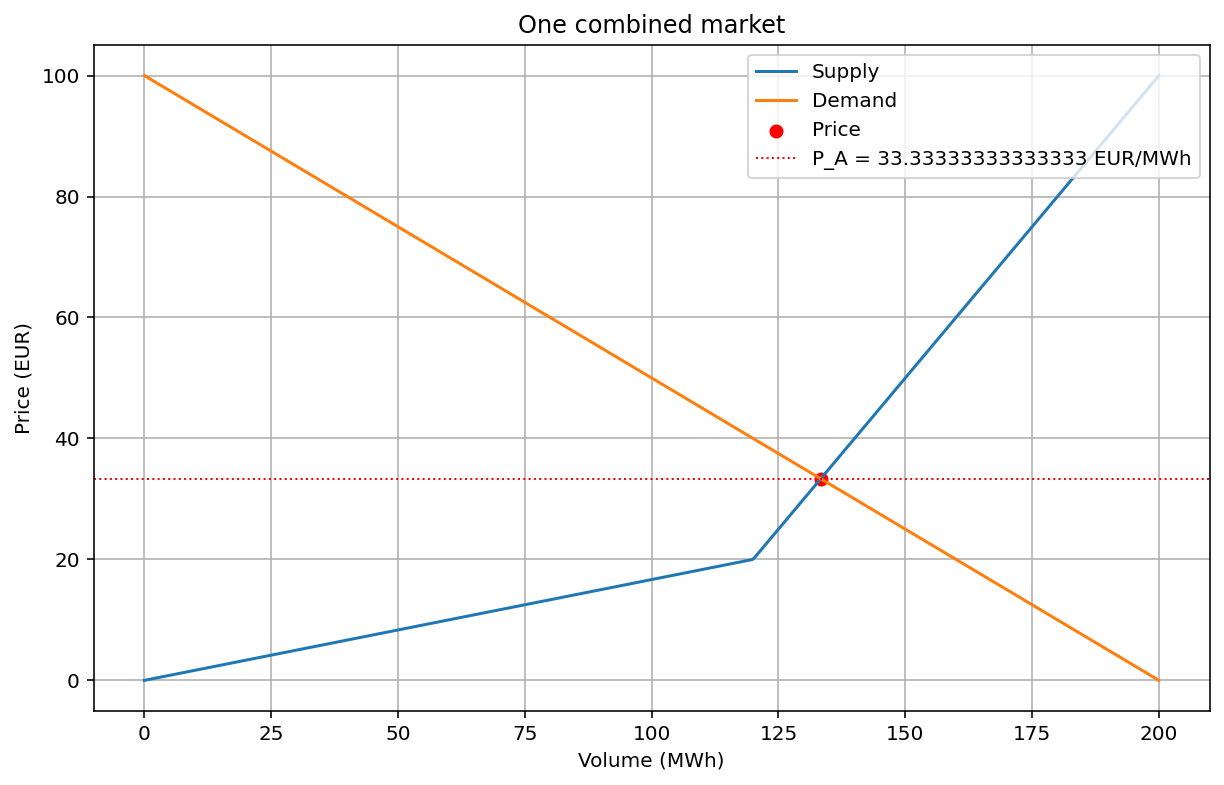

Merged market

Let’s look at what it would look like in a merged market, AB, where buy and sell bids are combined. Demand becomes D = 100 – v/2 in that market. The maximum bid is 100 in both markets and they decrease linearly down to 0, now at a maximum volume of 200. The supply becomes a bit more complicated, the cheapest bids come first and are followed by the more expensive bids. With a little reasoning, one can see that the combined supply becomes

S (v <= 100*(1+1/a)) = v/a/(1+1/a)

S (v > 100*(1+1/a)) = 100/a + (v – 100*(1+1/a))

That is, we have a lower price that is a combination of A’s bids and the lower part of B’s bids up to 150 (when a = 2), and then the bids continue to increase by 1 per unit. In that market, the following equilibrium is obtained

Cleared price 40.00

Cleared volume 120.00

Consumer Surplus 3600.00

Producer Surplus 2400.00

Total Welfare 6000.00

Luckily, in this combined market, we get the same price and volume as in the optimal case F = 20 for the two separated markets (with a = 2). So with a link of 20 or greater, A and B behave as a common market AB. And the utility is thus maximized.

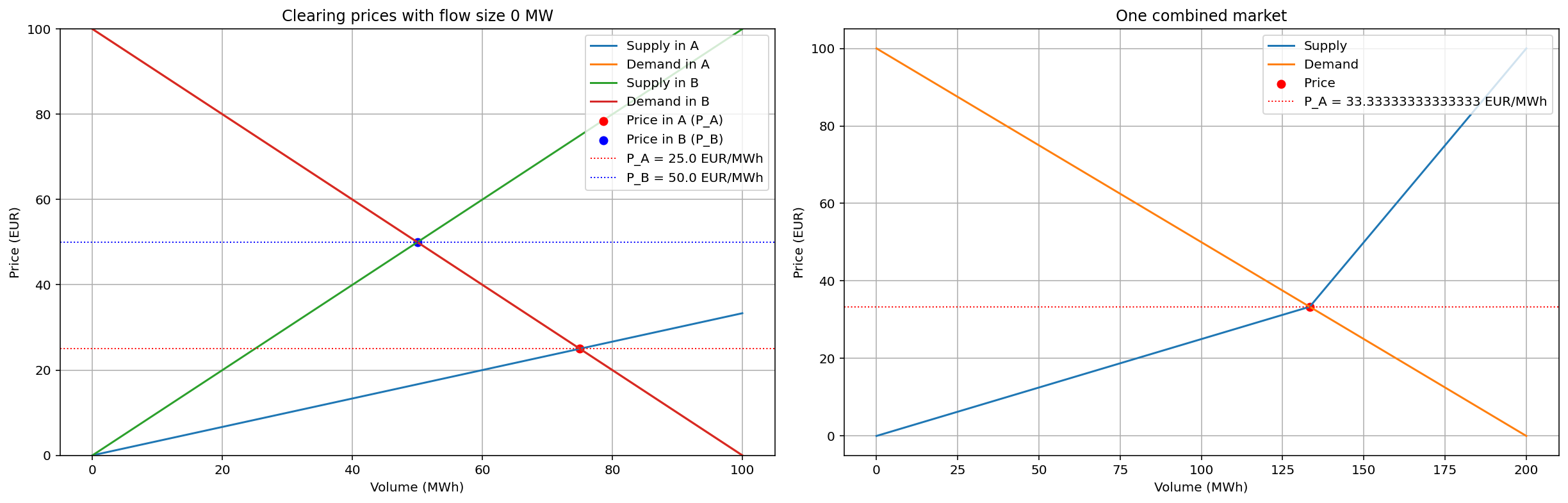

A is even more cheap than B, with a=3

If we instead use a = 3, i.e. make area A even more cheap than area B, and use the optimal flow 33.33333, the following equilibria are obtained:

Flow F A->B 33.33

Price in A 33.33

Price in B 33.33

Total volume 133.33

Consumer Surplus in A 2222.22

Producer Surplus in A 1666.67

Consumer Surplus in B 2222.22

Producer Surplus in B 555.56

Consumer Surplus 4444.44

Producer Surplus 2222.22

Congestion Rent 0.00

Total Welfare 6666.67

Cleared price 33.33

Cleared volume 133.33

Consumer Surplus 4444.44

Producer Surplus 2222.22

Total Welfare 6666.67

Price in A is 25, or half the price of B. Here, all capacity in A is utilized (66.67 to customers in A and 33.33 to customers in B). In B, only 33.33 is sold, the rest is imported from A. The total utility increases as the consumer surplus increases more than the producer surplus decreases, compared to the case a=2.

Constraining the flow

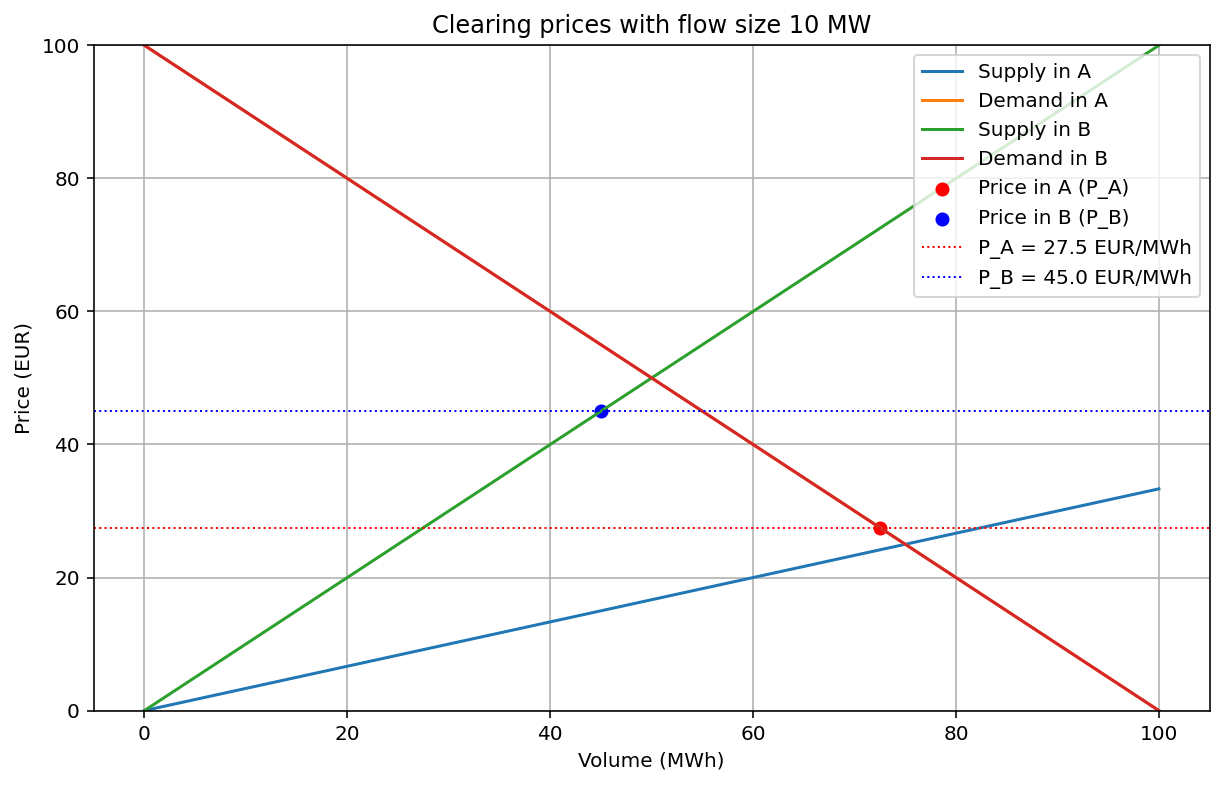

If we introduce a constraint, C (for capacity), so that F cannot be greater than C, then price parity cannot be obtained. For example, in this case (a = 3) we limit the flow to 10:

Flow F A->B 10.00

Price in A 27.50

Price in B 45.00

Total volume 127.50

Consumer Surplus in A 2628.12

Producer Surplus in A 1134.38

Consumer Surplus in B 1512.50

Producer Surplus in B 1012.50

Consumer Surplus 4140.62

Producer Surplus 2146.88

Congestion Rent 175.00

Total Welfare 6462.50

The price in the cheaper area A increases slightly, from 25 to 27.50, and decreases in area B. In this case we also a get a congestion rent, since prices in A and B differ. The difference is 17.50, and with a flow of 10, this congestion rent becomes 175. Typically, this congestion rent is split into two equal halves between the TSO’s in each area.

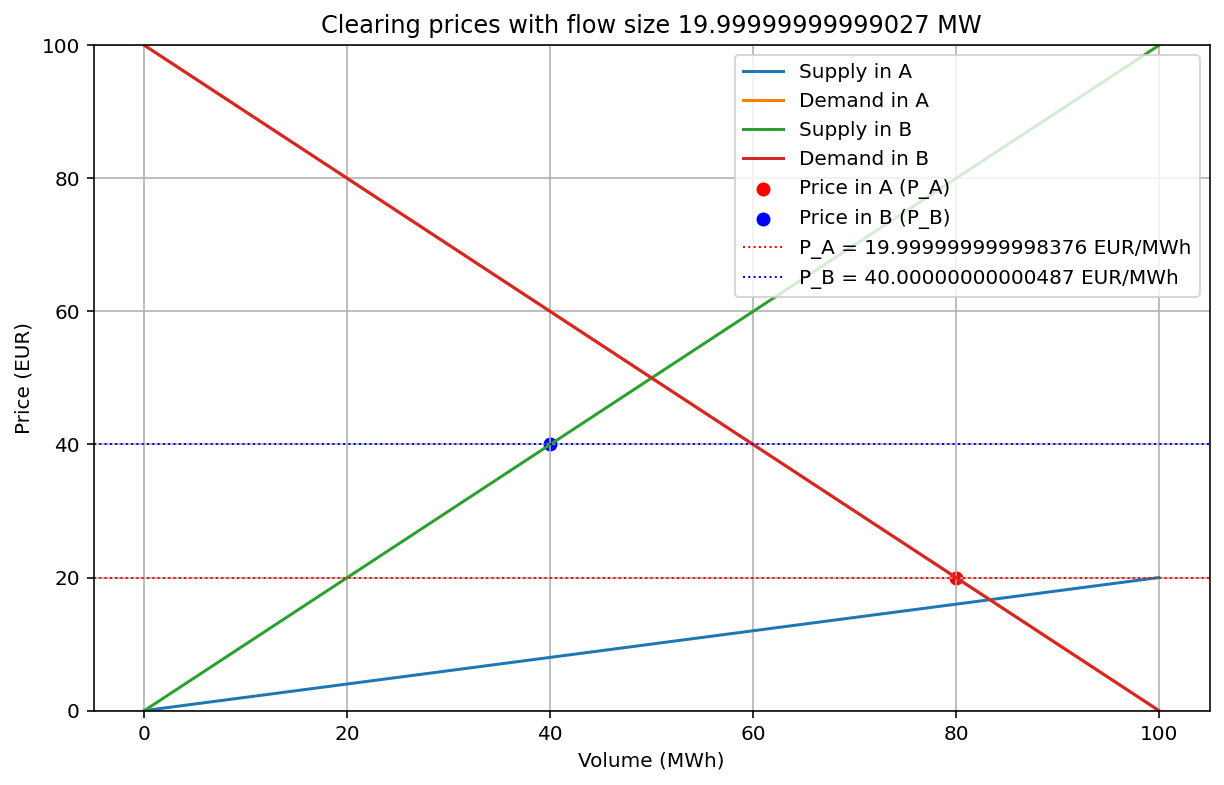

Export from A limited by maximum production in A

What happens if we lower prices even more in A? By using a = 5 for example? The problem we have here is that if we just use the simple formulas we have used up to now, A would like to set a price of 25 in both zones by exporting F = 50. The problem with this is that A would in this case consume (100 -25) = 75 and export 50, all in all have to produce 125, which is more than the 100 A can produce.

We thus have to introduce a constraint in that A’s consumption + export must be less or equal to its maximum production, which is 100. We could modify the equations for this, or we could just maximize the total welware, giving the constraint. The latter is done below:

Optimal F: 19.99999999999027

Maximized total welfare: 7199.999999999805

Flow F A->B 20.00

Price in A 20.00

Price in B 40.00

Total volume 140.00

Consumer Surplus in A 3200.00

Producer Surplus in A 1000.00

Consumer Surplus in B 1800.00

Producer Surplus in B 800.00

Consumer Surplus 5000.00

Producer Surplus 1800.00

Congestion Rent 400.00

Total Welfare 7200.00

As we can see, prices are not equalized between A and B, but the total welfare is the largest so far, because the low price in A pulls up the consumer surplus there. However, in reality it is unlikely that A shoud run out of supply, since what would happen is that the sell bids in A would increase strongly when approaching 100 in volume. The prices in A will then increase until there is price parity between A and B, but the flow F between A and B will be smaller.

If we compare this last case, with a = 5, to the same situation in the merged AB system we get a higher utility in the latter, reflecting that there are no restrictions in that case. The price will also stay at 33.33 for all a >= 3 in the merged model.

Cleared price 33.33

Cleared volume 133.33

Consumer Surplus 4444.44

Producer Surplus 2933.33

Total Welfare 7377.78

Summary

This was meant as a simple example of how markets interact with each other to obtain prices and flows. Considering how complex it becomes to do this calculation analytically, even in such a simplified case, we can see that it is very effective to instead use the possibility to maximize the total welfare, or utility, to obtain the prices within, and flows between the zones.

In order to do this for the coupled markets in Europe, the EUPHEMIA algorithm exists. It calculates clearing prices for all bidding zones, as well as the optimal flows between all zones and a lot of other stuff, with significantly more complicated bids and restrictions that exist in the real world. It is truly a remarkable feat.